Last night, PEN/Faulkner’s Summer Supper and Book Club looked at the happier side of the Depression as the group discussed Soul of a People: The WPA Writers’ Project Uncovers Depression America by David A. Taylor. Sharing their own associations of the Depression, Tiara and Takirra described bleak images of men, women, and families dying of starvation and disease. They weren’t expecting to see photos of jubilant barrel dancing or impassioned singing in the companion documentary to Taylor’s book. This kick started a broader discussion of the tricky task of writing history—and of deciding which images, events, traditions, and movements are deemed worthy of inclusion in textbooks and which (like the barrel dancers) are pushed to the background or omitted entirely.

Last night, PEN/Faulkner’s Summer Supper and Book Club looked at the happier side of the Depression as the group discussed Soul of a People: The WPA Writers’ Project Uncovers Depression America by David A. Taylor. Sharing their own associations of the Depression, Tiara and Takirra described bleak images of men, women, and families dying of starvation and disease. They weren’t expecting to see photos of jubilant barrel dancing or impassioned singing in the companion documentary to Taylor’s book. This kick started a broader discussion of the tricky task of writing history—and of deciding which images, events, traditions, and movements are deemed worthy of inclusion in textbooks and which (like the barrel dancers) are pushed to the background or omitted entirely.

We also tried put ourselves in the shoes of Depression-era taxpayers, assessing the merits of the Works Progress Administration Writers’ Project, which controversially employed writers to write comprehensive travel guides for American cities and regions. The question then (as today) was straightforward, if not uncomplicated: should the government pay writers to document and record the obscure Oneida language and the mule folktales of rural Southern communities? Are all cultural legacies worth preserving?

To provoke further inquiry, Ariel played the devil’s advocate by posing the question, “What’s wrong with everyone assimilating and speaking English?” Bre defended the United States as a nation that celebrates and preserves its diversity while Mecca questioned whether the US, in fact, valued all of its cultures.

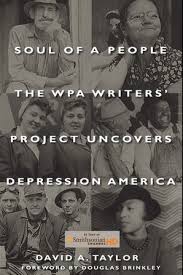

Students examine the WPA Guide to Washington, DC as David A. Taylor talks about the Federal Writers’ Project.

Conflicted about representations of history in their own textbooks, members of the book club were asked what they’d focus on if they were to write the history of the present. Our newest member, Donovan, talked about the importance of documenting music and the digital revolution, while Takirra thought it’d be important to document the election of Barack Obama as a pivotal moment in American history. David Taylor joined our discussion and spoke to the challenges of recording historical incidents and the even more complicated task of accurately recording the sentiments and mood that pervade certain moments in history. It’s one thing to report the economics of the Great Depression, but it’s quite another to look at the ways in which individual communities and subcultures reacted and adapted to it.

The writing assignment for the week was to create a WPA-style travel guide for their neighborhoods, and when Taylor asked members of the Book Club how the assignment had gone, the room went silent. What if their research approaches were wrong? What if they felt incapable or disallowed from writing a micro-history? Tatyana eventually broke the silence, and talked about approaching the assignment through the lens of her everyday life; for her, history was mostly about who she came into contact with. The fabric of her neighborhood was defined by its inhabitants, not merely its geography. Tiara shared that she’d interviewed relatives who could offer personal anecdotes about her neighborhood’s cultural history, and that the anecdotes she recorded had been told and re-told as neighborhood history for decades.

The evening ended as Taylor described a contemporary trend in which some writers may consider themselves either a playwright, a poet, a fiction writer, a journalist, a memoirist, etc. He noted that this wasn’t necessarily true for writers during the Depression, and so in approaching his own historical project (Soul of a People), he had to consider more broadly the categorical limitations of “fiction” or “nonfiction.” He pointed out that WPA writers like Richard Wright and Zora Neale Hurston were more fluid in their pursuits as writers and transitioned from research to novels to anthropological and sociological papers. We all walked away with a greater understanding of the subjective choices that drive the process of writing an official history, and of the important cultural information that can be lost, forgotten, or ignored in the process.

The evening ended as Taylor described a contemporary trend in which some writers may consider themselves either a playwright, a poet, a fiction writer, a journalist, a memoirist, etc. He noted that this wasn’t necessarily true for writers during the Depression, and so in approaching his own historical project (Soul of a People), he had to consider more broadly the categorical limitations of “fiction” or “nonfiction.” He pointed out that WPA writers like Richard Wright and Zora Neale Hurston were more fluid in their pursuits as writers and transitioned from research to novels to anthropological and sociological papers. We all walked away with a greater understanding of the subjective choices that drive the process of writing an official history, and of the important cultural information that can be lost, forgotten, or ignored in the process.

— Jack Nessman